Damming the Himalaya

(Enlarge to view captions)

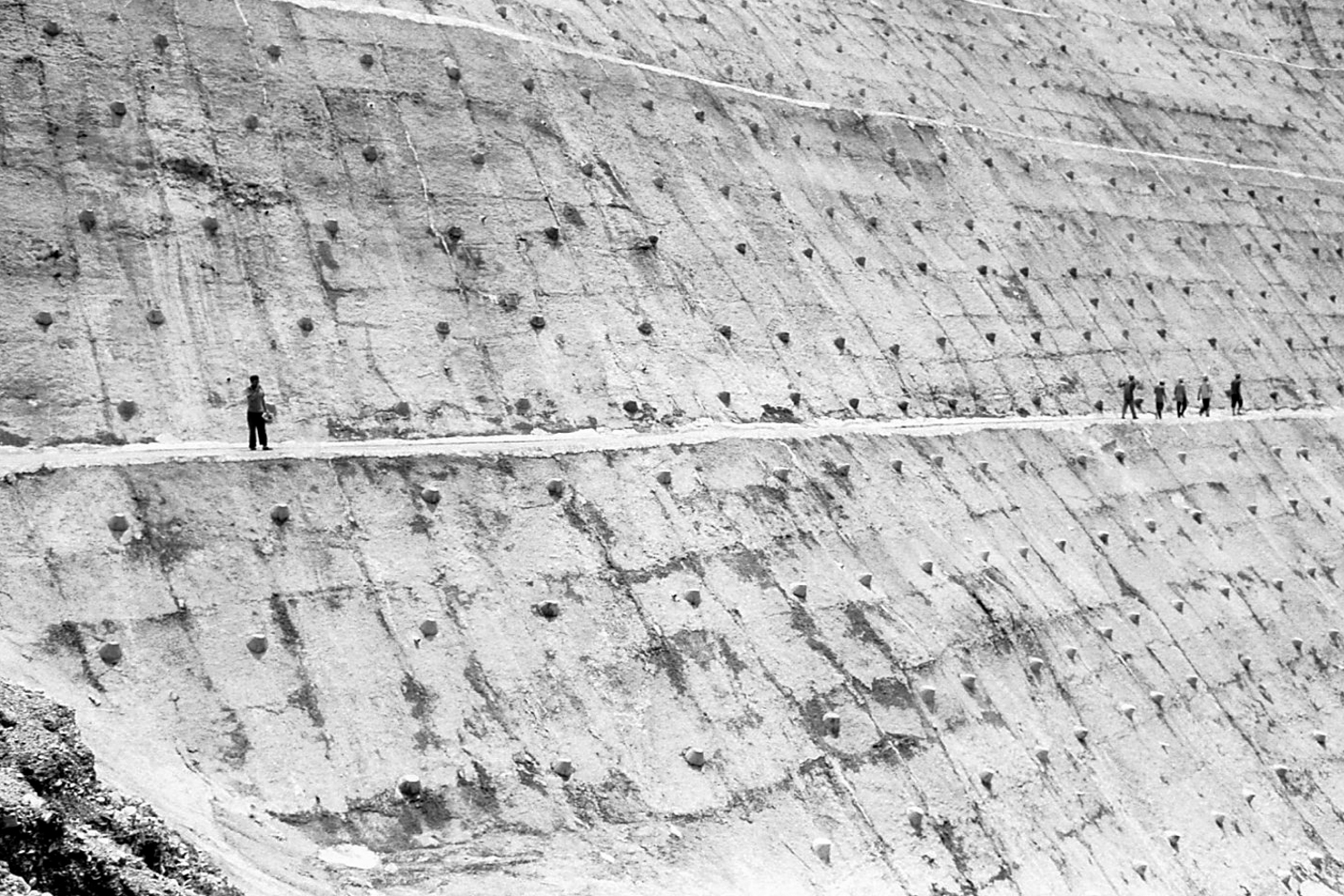

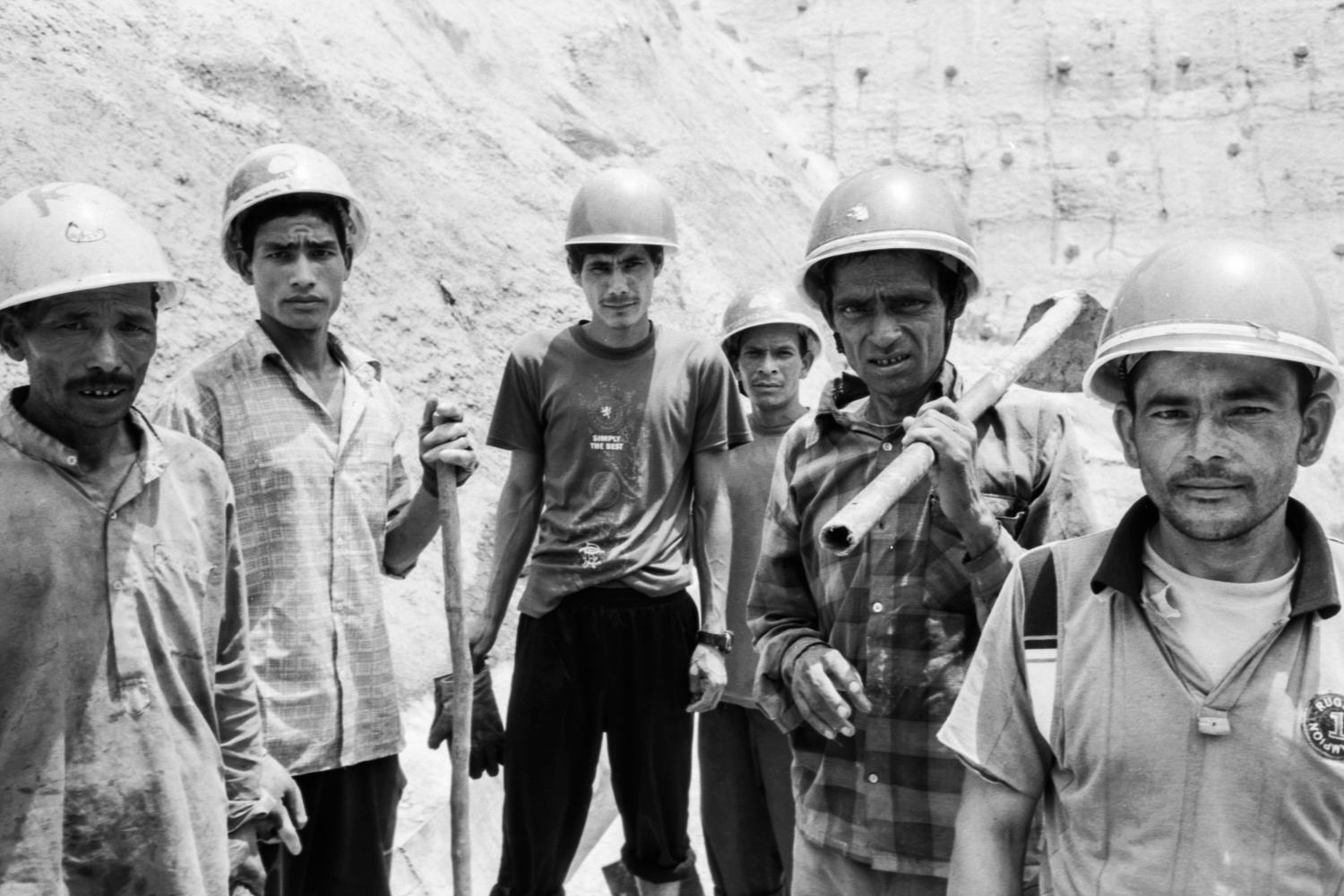

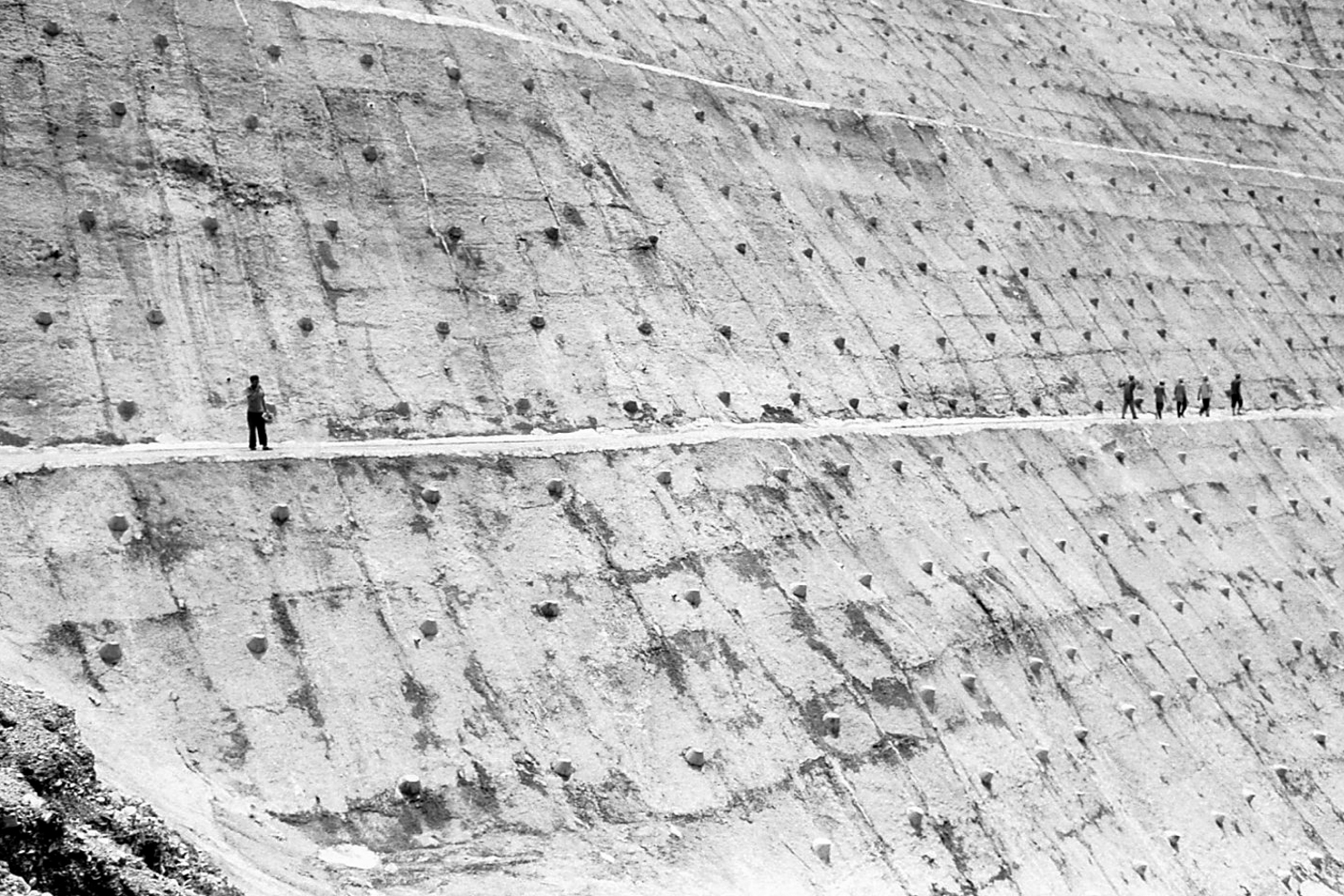

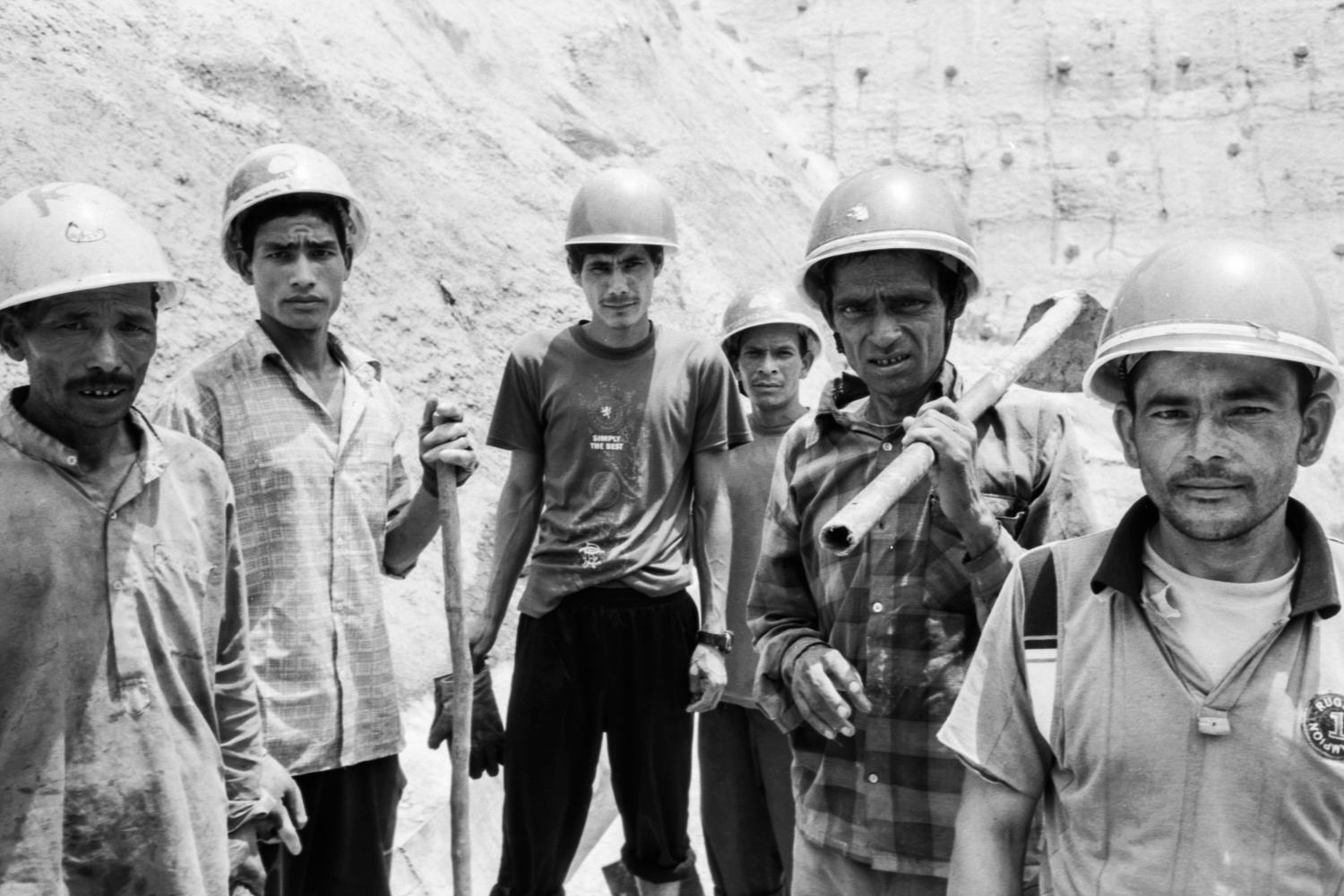

In 2011, I traveled alongside my friend and filmmaker Trevor Wallace to the site of the Chameliya Khola Hydropower Project in a remote valley in Nepal’s northwestern Darchula District, where the village of Balhast was disrupted by the construction of the large dam. These are photographs of the people whose lives were affected, in Balhast and neighboring villages. The photos accompanied the film by Trevor Wallace, Pani, which premiered at the World Water Forum in Marseille.

Chamelia is only one of innumerable Nepali hydropower projects. With a vast network of rivers rushing southward from the highest mountains in the world, Nepal boasts immense potential for hydroelectric power generation. Over the last two decades, the nation has seen a rapidly accelerating dam building boom; dozens of large dams have recently been completed, and yet these operational plants represent only a tiny sliver of the country’s hydroelectric potential. Over two hundred large hydropower projects are currently underway, mostly financed by China through their “Belt and Road” initiative.

The Nepali and Chinese governments present the dams as a win-win for their states, the local people, and the environment, promising benefits to the nearby poor, agrarian communities in the form of economic development and improved access to electricity. In reality—as we learned firsthand through conversations with the people of Balhast, as well as interviews with Nepali scholars and activists—these large dams mostly benefit their foreign financiers and imperil the local people.

Far from seeing improved economic prospects, many are displaced to the low-lying “Terai” region in Nepal’s south without compensation. Many of those who remain see their livelihoods ruined—the dams devastate local fish populations that the communities rely on, and disrupt access to the river water they need to irrigate their crops.

We spoke (through our friend and translator, Jagat) to a woman whose house had been destroyed by the floodwaters from the dam’s water diversion tunnels, a doctor who treated workers injured in the dam’s construction and through violent conflict with imported Chinese workers, farmers who could no longer water their crops, and many people whose friends and family had been displaced—promised a payment of one “lakh” (100,000 Nepali rupees, or about $750) that never came.

In Sipti—a neighboring village accessible only by foot up a steep mountain path—we encountered an alternative model of hydroelectric power generation. The sipti residents have a “micro-hydel,” a comparatively tiny, run-of-the river generator that provides electricity for the village without disrupting the river ecosystem. Everyone we spoke to in Sipti was happy with the small generator and the power it afforded them.

With the interests of local people in mind, the small-scale, collectively owned and operated generation of power is a far preferable means of electrifying Nepal’s rural population. Unfortunately, their well-being is more often than not ignored by the Nepali government and foreign financiers who seek profit by selling power to neighboring nations; micro-hydro projects are rare, and large dam construction is rapidly expanding across the nation.

All photos shot on a Leica M2 analog camera with black-and-white film. (I carried the rolls of film for a month in a garbage bag in my backpack, fearing the ubiquitous moisture of the monsoon season—which soaked all our belongings—would ruin the photos. Thankfully they turned out undamaged when I developed them.)

Chamelia is only one of innumerable Nepali hydropower projects. With a vast network of rivers rushing southward from the highest mountains in the world, Nepal boasts immense potential for hydroelectric power generation. Over the last two decades, the nation has seen a rapidly accelerating dam building boom; dozens of large dams have recently been completed, and yet these operational plants represent only a tiny sliver of the country’s hydroelectric potential. Over two hundred large hydropower projects are currently underway, mostly financed by China through their “Belt and Road” initiative.

The Nepali and Chinese governments present the dams as a win-win for their states, the local people, and the environment, promising benefits to the nearby poor, agrarian communities in the form of economic development and improved access to electricity. In reality—as we learned firsthand through conversations with the people of Balhast, as well as interviews with Nepali scholars and activists—these large dams mostly benefit their foreign financiers and imperil the local people.

Far from seeing improved economic prospects, many are displaced to the low-lying “Terai” region in Nepal’s south without compensation. Many of those who remain see their livelihoods ruined—the dams devastate local fish populations that the communities rely on, and disrupt access to the river water they need to irrigate their crops.

We spoke (through our friend and translator, Jagat) to a woman whose house had been destroyed by the floodwaters from the dam’s water diversion tunnels, a doctor who treated workers injured in the dam’s construction and through violent conflict with imported Chinese workers, farmers who could no longer water their crops, and many people whose friends and family had been displaced—promised a payment of one “lakh” (100,000 Nepali rupees, or about $750) that never came.

In Sipti—a neighboring village accessible only by foot up a steep mountain path—we encountered an alternative model of hydroelectric power generation. The sipti residents have a “micro-hydel,” a comparatively tiny, run-of-the river generator that provides electricity for the village without disrupting the river ecosystem. Everyone we spoke to in Sipti was happy with the small generator and the power it afforded them.

With the interests of local people in mind, the small-scale, collectively owned and operated generation of power is a far preferable means of electrifying Nepal’s rural population. Unfortunately, their well-being is more often than not ignored by the Nepali government and foreign financiers who seek profit by selling power to neighboring nations; micro-hydro projects are rare, and large dam construction is rapidly expanding across the nation.

All photos shot on a Leica M2 analog camera with black-and-white film. (I carried the rolls of film for a month in a garbage bag in my backpack, fearing the ubiquitous moisture of the monsoon season—which soaked all our belongings—would ruin the photos. Thankfully they turned out undamaged when I developed them.)